Filling the Gaps: MapGive Imagery Services Enhance Humanitarian Mapping

More recent quality imagery assists new mapping

Maps and geographic data feed into nearly every stage of the humanitarian response cycle, from operational planning in the field to strategic gap analyses by coordination officials. In 2012, the Humanitarian Information Unit (HIU) began implementing a workflow called Imagery to the Crowd (aka “IttC”) to provide U.S. Government-purchased commercial satellite imagery to the humanitarian OpenStreetMap (OSM) community. At the time, the available satellite imagery allowing volunteers to map features was limited or expensive, and often lacked the resolution needed for mapping in areas prone to natural disaster and conflict-related displacement. IttC filled a critical gap in the humanitarian mapping ecosystem by publishing current, high-resolution imagery from DigitalGlobe in a user-friendly web-based format.

MapGive’s launch in 2014 coalesced and re-branded the HIU’s efforts to support crowdsourced humanitarian mapping. By building on IttC, Mapgive is a more ambitious endeavor to leverage the U.S. Department of State’s vast global reach and encourage more active volunteer participation in the global mapping community. We continue to provide a reliable imagery support service to those leading and designing volunteer mapping projects around the world, most recently in Uganda and Bangladesh in response to rapidly growing refugee crises. Since its inception, MapGive efforts have facilitated more than three million edits to OSM by nearly thirty five thousand volunteers, primarily for mapping projects designed to directly assist people in need (explore our interactive data dashboard for more details).

Today, mappers have access to a wider variety of satellite imagery services, as companies like DigitalGlobe, Mapbox, Esri, and others have also opened their proprietary imagery services to facilitate the creation of foundation geographic data in OSM (e.g., DigitalGlobe, through its Open Data Program, frequently responds to natural disasters by publicly releasing its imagery). The impact has been felt across the community as more diverse imagery sources help to lower the barrier of entry in generating useful mapping projects in remote parts of the globe, whereas historically one might face challenges in identifying suitable imagery for a specific project.

Despite the increasing availability of free imagery services, MapGive adds value in more discrete contexts, particularly where the available imagery is not sufficient in capturing recent developments on the ground and when satellite companies have not publicly released their imagery. During two recent humanitarian emergencies, in Uganda and Bangladesh, MapGive-provided imagery formed the backbone of sustained mapping campaigns over areas affected by the influx of refugees from South Sudan and Burma, respectively. In both cases, the volunteer community of “citizen mappers” quickly mobilized to support humanitarian agencies responding to the world’s fastest growing refugee crises.

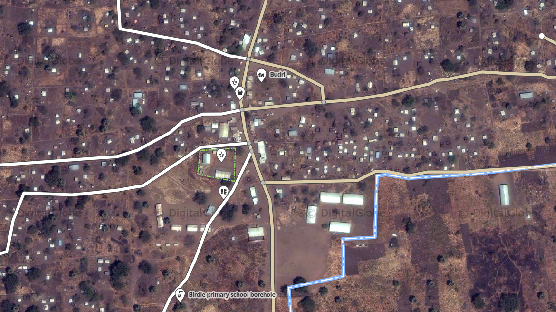

MapGive responds directly to imagery needs identified by the humanitarian mapping community, which is rooted in our policy for sharing satellite imagery with trusted partners. By working with Missing Maps in Uganda, for example, we were able to publish current imagery to support mapping projects designed by humanitarian organizations working directly in refugee settlements (see the image example below from Palorinya refugee settlement in northern Uganda). In a matter of days, online volunteers mapped hundreds of thousands of shelters, roads, and camp facilities to facilitate further data attribution and validation in the field, which became integral to the UN-coordinated response in both contexts (see this Reuters story for illustrative examples from Bangladesh).

Initially, the rapidly expanding refugee settlements needed to be mapped to assist in designing critical infrastructure such as emergency health clinics, water and sanitation centers, and food distribution points. Later, multiple UN agencies and NGOs (including IOM, UNHCR, IFRC, MSF, REACH, HOT and others) continued to update the baseline geographic data and leverage it for the response.

Today we have a more refined blueprint and mechanism to enable the rapid mapping of emerging settlements for civilians displaced by conflict. The significant growth of available imagery providers has been a tremendous success for the crowdsourced mapping community, and within that growing ecosystem MapGive continues to be a relevant and useful source of support—particularly in situations that require current satellite imagery—and capitalizes on the vast global reach of the U.S. Department of State to attract new mappers and facilitate participation in the wider community.

Before and After visualization of OpenStreetMap around refugee camps in Northern Uganda